A Re(new)ed Brotherhood

As the drudge of 2020 came to a long-awaited close, 2021 rolled in with little goodness to offer. With the world’s eyes focused on America’s Next Twitter Disaster, few paid attention to the “progress” in the Gulf. On the 5th of January, Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, Egypt, and UAE lifted sanctions placed on Qatar and formally ended the diplomatic blockade that began in June 2017. After disagreements with the Qatari government regarding their alleged sponsoring and supporting of militia and terror cells, their biased coverage of Gulf news and interference in Egyptian and Lebanese politics, the GCC decided to bury the hatchet.

Well, at least they seem to be.

But after three and a half years, what’s in it for Qatar?

In its state of isolation, the Qatari government has had to take many new steps and policies to keep its economy running. Qatar’s foreign direct investments (FDIs) dropped substantially as an immediate consequence of the embargo, recording a 321.73% decline in 2018. Their foreign supply chain for domestic food, which accounted for 90% of the national consumption, became vulnerable. Citizens began to panic purchase, food was scarce, and the nation was militarily compromised. These provoked the government to make quick, important decisions to keep the country running.

Qatar accelerated efforts to diversify sources of imports and external financing. It took assistance from neighbours Turkey – who were in opposition to the GCC’s actions – and received dairy and poultry in less than 48hours after the imposition of sanctions. Amid an acute food crisis and shortage of basic amenities, Turkish exports increased by 90% in the first four months. Qatar’s relationship with Iran and Turkey and Kuwait and Oman's neutral standpoint allowed it to re-establish various trade links, which previously used Arabian routes. Though this increased the time of movement and raised costs, it provided food on the table for many. As a more sustainable measure, Qatar adopted a self-sufficiency model for the dairy industry, and companies like Baladna and Agrico had to adapt quickly to achieve this. Today, the Qatari economy, which once imported 72% of its dairy demand, produces it on its own in the northern

region, where fodder and groundwater are plentiful. Furthermore, Qatar invested $444m in a 530,000 sq.m food storage and processing facility at the Hamad Port and aimed at producing 60% of its total food demand by 2020. Such steps were beneficial for densely populated areas like al-Rayyan and al-Khor, which suffered from food shortage during the blockade’s early phases.

Following rumours of the Saudis and the Emiratis’ plan to annex Qatar, which was abandoned due to diplomatic pressure from then-US Secretary of State Rex Tillerson, the Qatar Emiri Air Force (QEAF) expanded its military power with new trade deals in the West. Their once meagre air force, which contained only 12 Dassault Mirage 2000s and half a dozen Alpha light trainers, now comprises British Typhoon jets worth $8billion, French Dassault Rafale, AH-64 Apache helicopter gunships along with C-17, C-10 transporters. The Pentagon awarded Boeing a $6.2 billion contract to manufacture 36 new F-15QAs for the QEAF by 2022 as part of its $12bn deal signed in June 2017 – a move that could soon make Qatar a significant military concern to the Saudis and Emiratis. QEAF expanded its Al Udeid Air Base to house many Qatari, American, British and Gulf Coalition forces – an investment of $1.8 billion, making the biggest Western airbase in the Middle East even bigger. Qatar also strengthened its naval position through a €4bn alliance with Fincantieri S.p.A which would ensure the delivery of 10 surface vessels by 2026.

As the Middle East faces a rapid surge in domestic energy demands due to infrastructural and economic growth, Qatar began to expand its LNG trade across Asia and Europe during the blockade. The industrial hub of Ras Laffan played a large role in this endeavour. In fact, in 2019, Qatar decided to leave the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) to morph its oil economy into a self-sufficient one. Diplomatic relations with Iran gave it access to the Strait of Hormuz for trading with the Asian market, while the trade embargo forced ships to travel to Europe around the Cape of Good Hope. With higher transportation costs, the oil and natural gas industry took a hefty short-term hit but irregularities in oil prices and stocks.

But, they used the opportunity to inflate its long-run economic strategy.

Qatar currently has an LNG production capacity of some 77 million megatonnes per year (Mt/year) and plans to raise it to 100 million Mt/year by 2027 with six new trains. Qatar Petroleum (QP) has also launched an LNG trading arm that could target shorter-term volume placements on a global scale. It reaffirmed its commitment to the UK gas market through a 25-year agreement for up to 7.2 million Mt/year of import capacity. It laid the screws on long-term projects in France and Belgium, further boosting its economy until the middle of the 21st century.

While many sectors have been able to keep things at bay, some have taken gigantic blows. Growth in tourism – which in 2017 recorded a 25.13% increase – fell by 3.29% after the blockade. Furthermore, the COVID -19 lockdown caused a 30% drop in the first quarter of 2020.

In the immediate aftermath of the embargo, nationals from 80 countries were given visa-free entry. The development of the Qatar National Museum and expansion of the Hamad International Airport and other tourist attractions were also expedited. But none of these measures was sufficient enough to keep the tourism sector profitable. Many reckon that Qatar’s hosting of the FIFA World Cup (FWC) in 2022 would tip the scales in their favour – with increasing foreign direct investments and surging tourism from across the globe.

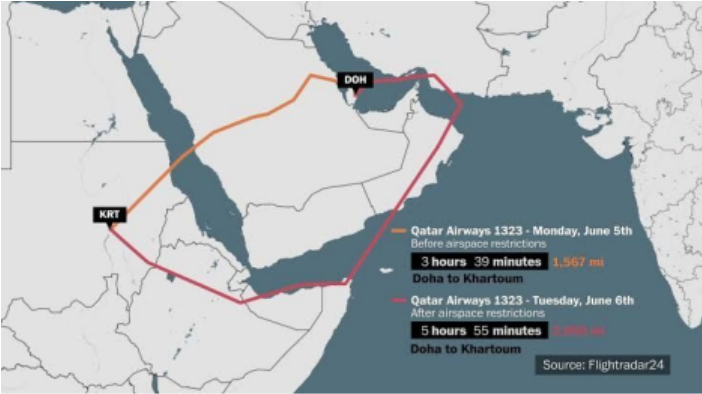

The national airline, Qatar Airways (QA), lost roughly 50 flights a day and 18% airlines total seating capacity. In 2017, Airline Weekly called it “the fourth-worst performance in the entire global airline industry”. They had to cancel Airbus A350 deliveries worth $1.2 billion and declared a $703 million operating loss for the FY2017, despite receiving $500 million in subsidies. To compensate for lost Gulf destinations, QA added new flights to the Czech Republic, France, Macedonia, Oman, Australia, Brazil, and Chile. It also paid Iran $100million/year during the travel ban to use its airspace.

But this had little effort because net flight costs were expensive nonetheless. As per QCAA (Qatar Civil Aviation Authority) regulations, a new air-crew must replace an existing one when it exceeds its maximum permitted log – even if it's mid-air. As airspace restrictions forced flights to take new and longer routes (as shown below), fuel consumption rose, additional crew finances had to be accounted for, and net additional costs took a spike.

It is important to note that the blockade has heavily sapped the Qatari treasury. In keeping industries running and bailing out banks, real-estate prices and salaries of foreign workers have dropped significantly. While Qatar has expanded its global connections amid Arabic isolation,

the 2021 reconciliation agreement is a welcome handshake – one that they might want to squeeze with ripe smiles.

The agreement stands as a move to bolster the economic interests of Gulf nations. Qatar’s refusal to accede to the thirteen demands of the GCC stands with little chance of changing. The International Energy Agency (IEA) in 2017 claimed that the Gulf spat led to logistical headaches with growing shipping costs for all GCC members, forcing each nation to take close attention to self-sufficiency. It was as if the Gulf States had moved from the stage of cooperation to a state of self-reliance.

The reconciliation agreement is perhaps a symbol of the failure of such a model. As a matter of fact, it portrays the inability of the Saudi Arabian clout and makes Qatar the noisy neighbours everyone must be wary of. With QA demanding a $5 billion compensation payment from the GCC and many more nuanced aspects of the agreement left to be ironed out, this deal is by no means an olive branch just yet.

Qatar’s position with Iran and Turkey is of particular concern to the GCC, and it will be interesting to see how the Arabian political dynamic would play now. Before the blockade, Doha had concerns about Iran filling more regional power vacuums and raising sectarian temperatures instability in the Gulf. Thus, Qatar has been careful in maintaining a pragmatic partnership with the Iranians. Sheikh Tamim could use these gains to ensure a more prominent role for Doha in regional affairs. Having built on Qatari-Irani relations, he might be able to present himself to newly-elected POTUS Joe Biden as the preferred intermediary to establish better diplomatic relations with Tehran after the collapse of the Joint Comprehension Plan of Action (i.e. the Iran nuclear deal).

The turn of the new year could result in a renewed unity amongst the Arab nation - or further turmoil and hegemony.

The die has been cast.

Written by Abhik Chatterjee

References

1. Gulf plunged into diplomatic crisis as countries cut ties with Qatar. (2017, June 5). The Guardian. Retrieved from

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/jun/05/saudi-arabia-and-bahrain-break-diplom atic-ties-with-qatar-over-terrorism

2. Reuters Staff. (2021, January 19). Qatar’s foreign minister wants Gulf Arab nations to talk with Iran: Bloomberg. Reuters. Retrieved from

https://www.reuters.com/article/gulf-qatar-iran/qatars-foreignminister-wants-gulf-arab-na tions-to-talk-with-iran-bloomberg-idUSFWN2JT0NC

3. Alterman, J. B. (2021, January 5). GCC Rift over Qatar Comes to an End. CSIS. Retrieved from https://www.csis.org/analysis/gcc-rift-over-qatar-comes-end 4. Arab states issue 13 demands to end Qatar-Gulf crisis. (2017, July 12). Al Jazeera. Retrieved from

https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2017/7/12/arab-states-issue-13-demands-to-end-qatar-g ulf-crisis

5. What are the 13 demands given to Qatar? (2017, July 23). Gulf News. Retrieved from https://gulfnews.com/world/gulf/qatar/what-are-the-13-demands-given-to-qatar-1.204811 8

6. Iddon, P. (2020, December 22). Qatar Will Emerge From Saudi-Led Blockade With A More Powerful Military Than Ever. Forbes. Retrieved from

https://www.forbes.com/sites/pauliddon/2020/12/22/qatar-will-emerge-from-saudi-led-bl ockade-with-a-more-powerful-military-than-ever/?sh=582774191ded

7. Emmons, A. (2018, August 1). SAUDI ARABIA PLANNED TO INVADE QATAR LAST SUMMER. REX TILLERSON’S EFFORTS TO STOP IT MAY HAVE COST HIM HIS JOB. The Intercept_. Retrieved from

https://theintercept.com/2018/08/01/rex-tillerson-qatar-saudi-uae/

8. Malsin, J. (2018, December 1). Qatar Builds Up Military, Spurred by Saudi-Led Blockade. The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved from

https://www.wsj.com/amp/articles/qatar-builds-up-military-spurred-by-saudi-led-blockad e-1543515441

9. Pentagon: Boeing wins $6.2bn contract for Qatar’s F-15. (2017, December 23). Al Jazeera. Retrieved from

https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2017/12/23/pentagon-boeing-wins-6-2bn-contract-for-q atars-f-15

10. Browne, R. (2017, June 15). Amid diplomatic crisis Pentagon agrees $12 billion jet deal with Qatar. CNN. Retrieved from

https://edition.cnn.com/2017/06/14/politics/qatar-f35-trump-pentagon/index.html 11. Taylor, A. (2019, August 21). As Trump tries to end ‘endless wars,’ America’s biggest Mideast base is getting bigger. The Washington Post. Retrieved from

https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/as-trump-tries-to-end-endless-wars-americas-big gest-mideast-base-is-getting-bigger/2019/08/20/47ac5854-bab4-11e9-8e83-4e6687e9981 4_story.html

12. Boeing’s F-15 Qatar Advanced Jet Completes Successful First Flight. (2020, April 14). Media Room. Retrieved from

https://boeing.mediaroom.com/2020-04-13-Boeings-F-15-Qatar-Advanced-Jet-Complete s-Successful-First-Flight

13. FINCANTIERI STRENGTHENS THE STRATEGIC PARTNERSHIP WITH QATAR. (n.d.). Fincantieri. Retrieved from

https://www.fincantieri.com/en/media/press-releases/2020/fincantieri-rafforza-la-partners hip-strategica-con-il-qatar/

14. Elliott, S. (2020, November 13). FEATURE: Set for huge capacity expansion, Qatar eyes new LNG homes. SP Global. Retrieved from

https://www.spglobal.com/platts/en/market-insights/latest-news/coal/111320-feature-set-f or-huge-capacity-expansion-qatar-eyes-new-lng-homes

15. Qatar Tourism Statistics 1999-2021. (n.d.). Macro Trends. Retrieved January 21, 2021, from https://www.macrotrends.net/countries/QAT/qatar/tourism-statistics 16. How Turkey stood by Qatar amid the gulf crisis. (n.d.). Al Jazeera. Retrieved January 21, 2021, from

https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2017/11/14/how-turkey-stood-by-qatar-amid-the-gulf-cr isis

17. Qatar’s government pushes a food sustainability agenda. (2017, November 25). Oxford Business Group. Retrieved from

https://oxfordbusinessgroup.com/news/qatar%E2%80%99s-government-pushes-food-sust ainability-agenda

18. Wellesley, L. (2019, November 13). How Qatar's food system has adapted to the blockade. Chatham House. Retrieved from

https://www.chathamhouse.org/2019/11/how-qatars-food-system-has-adapted-blockade 19. The GCC crisis and qatar airways. (2017, August 13). INTERNATIONAL POLICY DIGEST. Retrieved from https://intpolicydigest.org/2017/08/13/gcc-crisis-qatar-airways/ 20. BERESNEVICIUS, R. Y. T. I. S. (2019, December 17). In-depth: Qatar airways global expansion despite blockade. Aerotime. Retrieved from

https://www.aerotime.aero/24351-qatar-airways-strategy-blockade

21. Bearak, M. (2017, June 8). Three maps show how the qatar crisis means trouble for qatar airways. The Washington Post.

https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/worldviews/wp/2017/06/07/three-maps-explain-h ow-geopolitics-has-qatar-airways-in-big-trouble/

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------