Beyond Numbers: India’s triumph over poverty in a population boom

INTRODUCTION

Population explosion and inequality have been two of the most burning contemporary issues to policymakers causing hindrances to effective policy implementation and incorrect stakeholder analysis. Population and poverty issues go hand in hand wherein a proliferation in population causes a dearth of coffers, leading to unstable wealth distribution and exacerbated poverty. This composition draws out the pressing relationship between population and poverty problems through economic models given by prestigious economists and aims to show the role of these indices in shaping public policy. The article highlights the aspects in which demographic trends can affect public policy and be a major determinant in analyzing if the policy successfully brings the asked results. It substantially focuses on India’s take on eradicating poverty in recent times despite being a developing country faced with major hindrances. It also highlights any disagreement present in the policy brought about in the country to battle poverty and measures to be espoused to foster better inclusivity.

Inferring the relationship between Poverty and Population

Various economic models show that population growth and economic growth are inversely related and with increments of population and fallout of demographic trends, economic growth follows a falling line.

Early Models showed the inevitable growth of the population Malthus argued that population and resources maintain a homeostatic balance: if living conditions permit, the population will grow until it’s restrained either by the - preventative check of controlling reproduction or by resource dearths resulting in positive checks. This was grounded on the supposition that the supply of key factors of production was largely fixed.

Mid-twentieth-century models of profitable growth indicated that increases in population growth constrain growth in income per capita. The Harrod-Domar model showed that in the absence of diminishing returns to capital, income growth- per capita is affected negatively by population growth and appreciatively by savings and increases in the output-capital ratio. Solow assumed that both capital and labor had diminishing returns, and illustrated that an exogenous increase in the population growth rate would restate into a growth of labor supply that would outpace the growth of capital formation and eventually lower per-capita income. Coale and Hoover modeled the relationship between population growth and economic development for India in the 1950s, naming it to be a low-income country then, and concluded that a rise in population growth may negatively affect economic development indicators due to the adding size of the population and high child dependency ratios. However, this model faced a lot of empirical challenges.

Modern-century models Higgins and Williamson set up that high youth dependency ratios were associated with lower savings and investment. Bloom and Williamson argued that the rapid fertility decline in East Asia facilitated the rapid economic growth in this region by reducing the dependency ratios – thereby expanding the per capita productive capacity of East Asian economies. Kelley and Schmidt (2005) conclude that high dependency rates (including both youth and old-age dependency ratios) significantly impact growth. They find that - Worldwide, the combined impacts of demographic change have been reckoned for roughly 20% of per capita output growth impacts, with larger shares in Asia and Europe.

Though these dynamics and debates concentrate on the relationship between prosperous population growth and consequent decline in economic growth, it’s relatively apparent that they view economic growth as a means to raise living standards and reduce poverty. Also, an integral part of economic growth is the enhancement of human development indices, which in turn boils down to majorly reducing poverty. For, a country like India, still floundering to stay put on its development path and striving continuously to become an advanced country battling with limited coffers and fiscal crunch, it’s quintessential that eradication of poverty and effective poverty measurement shall serve as a mark for fostering inclusive growth for all. Further, more population results in more mouths to feed and the prevailing inequality in developing countries forces low-income groups to claw into poverty. Looking at economic growth through prosperity in the total GDP of a country can hence, be deceiving and steps should be taken to measure inclusivity in the development indicators.

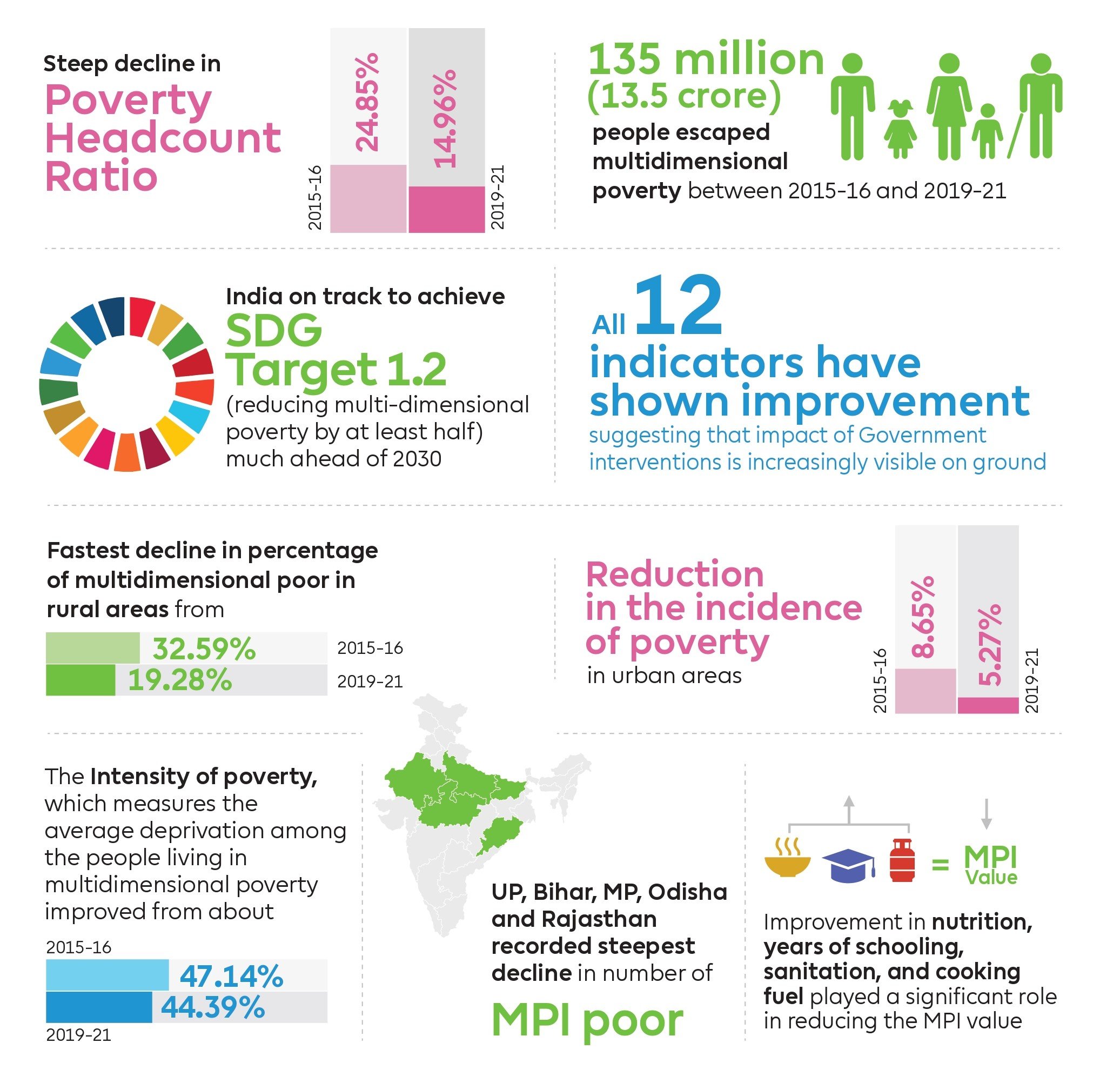

According to a recent report published by the NITI Aayog, India has registered a significant decline of 9.89 percentage points in the number of India’s multidimensionally poor from 24.85% in 2015-16 to 14.96% in 2019-2021. The rural areas witnessed the fastest decline in poverty from 32.59% to 19.28%. During the same period, the urban areas saw a reduction in poverty from 8.65% to 5.27%. Between 2015-16 and 2019-21, the MPI value has nearly halved from 0.117 to 0.066 and the intensity of poverty has reduced from 47% to 44%, thereby setting India on the path of achieving the SDG Target 1.2 (of reducing multidimensional poverty by at least half) much ahead of the stipulated timeline of 2030. It demonstrates the Government’s strategic focus on ensuring sustainable and equitable development and eradicating poverty by 2030.

However, as we all are aware, India surpassed all the nations in the world in terms of population and this article has previously established the negative relationship between population growth and the rise in poverty. So, what led to this anomalous change for a developing country like India, which despite moving towards becoming the most populous country in the world, has managed to work with striding steps towards effective poverty eradication, is a matter noteworthy of discussion and debate.

Demographics and Public Policy in an Indian Context

Source: NITI Aayog,National Multidimensional Poverty Index,A Progress Review, 2023

Major schemes contributing largely to this progress achieved and their critical analyses is as discussed below

Pradhan Mantri Ujjwala Yojana (PMUY) This scheme was enforced in May 2016 and aimed to give free LPG gas connections to 80 million poor homes by March 2020 and achieved its target in September 2019 (Press Trust of India 2019). This notable achievement is reflected in a decline in deprivation due to having cooking gas from 65.59% (2014 – 15) to 44.34% (2017 – 18). The perpetuation of the scheme led to the growth of household LPG content fleetly to reach 94.3% as of April 1, 2019. However, pressing concerns regarding the scheme stated that a significant number of the scheme’s BPL beneficiaries didn’t use the service beyond the initial refill, substantially due to economic reasons. Despite comprehensive coverage of the scheme, more than half the beneficiaries consumed less than the public normal of 3.21 refills. However, the proliferation in consumption of single-cylinder consumers to 2- 20 refills a day suggests a diversion to commercial use and indicates that numerous homes regressed to traditional energies due to the easier availability of similar energies and the higher price of LPG refills, despite them being unclean. The government should take visionary measures to ensure that safer cooking fuels similar to electricity and LPG end up as the compulsory option for all the homes in the country and act towards ensuring sustainability, as, despite an overall enhancement in this arena, there has been a lack of inclusivity on an individual basis.

Samagra Shiksha Abhiyan (SSA) This flagship scheme contained three other schemes (Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan, Rashtriya Madhyamik Shiksha Abhiyan, and Teacher Education) and concentrated towards improving education, years of schooling, and literacy rates. The result of such interventions was average years of formal schooling for those 15 years and aged reaching 9.7 years in 2017 – 18 and an attendance rate of nearly 94% for the 6 – 14 age group. The result of these interventions can also be seen in the decline of privation on account of years of schooling from 11.1% (2014 – 15) to7.93% (2017 – 18) and attendance rate from 7.28% (2014 – 15) to 5.47% (2017 – 18). However, the quality of education remains a concern. There’s a lack of responsibility under SSA which manifests itself in poor literacy issues and attendance rates of teachers and the lack of infrastructural installations is a bottleneck in the perpetration. The NSSO-75 education schedule reveals that 13.6% of individuals aged 15 years and over are not enrolled in any education due to lack of interest and fiscal constraints, another resource-dearth problem for a developing country. Hence, the government should ensure that these petty gaps are met and desired outcomes are achieved.

The National Health Mission (NHM) and The Ayushman Bharat Scheme The Ayushman Bharat scheme was launched in 2018 to help around 50 crore Indians access good quality and affordable healthcare. Ayushman Bharat Pradhan Mantri Jan Arogya Yojana (PM-JAY), with one crore treatments as of May 2020, has formerly appreciatively impacted numerous lives, making healthcare affordable and accessible. Under this scheme, a beneficiary can mileage free medical benefits up to Rs 5 lakh per family per time. The drawbacks of this scheme include a lack of awareness, inadequate IT structure, and inaccessibility. The government of India introduced the National Rural Health Mission in 2005- now converted into the National Health Mission (NHM), to bring about architectural reforms in the health sector. The IMR, MMR, and total fertility rate have bettered over the last decade through the sustained efforts of NHM. Despite the sweats, significant geographic injuries in the issues are still observed. This has been reportedly due to variations in scale-up problems related to crunches in human resources & infrastructure, poor convergence, lack of community participation, and finance flow mismanagement.

There’s a need to ensure better policy penetration through better stakeholder analysis of these schemes so that they reach the concerned millions in the asked way.

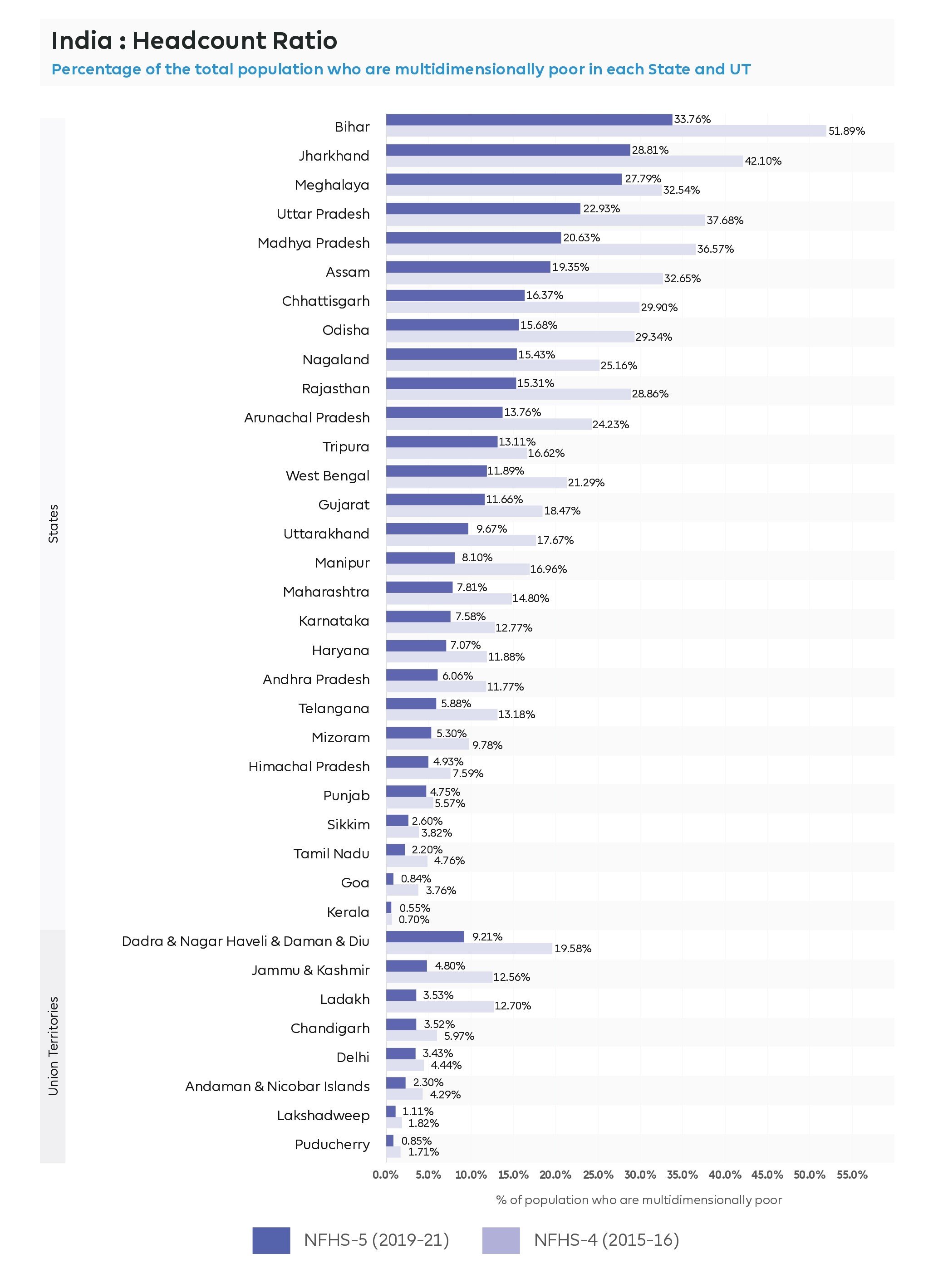

Hence, the stressed schemes had a major contribution to the milestones achieved by India but the failings need to be addressed for a perfect outgrowth. Indian policymakers need to take targeted interventions to reduce the MPI further and push the country towards sustainable development. The image shows the reduction in MPI formerly achieved by India across various states:

Source: NITI Aayog,National-Multidimentional-Poverty-Index,A Progress Review, 2023

CONCLUSION

The composition looks at how demographics are an integral part of public policy by taking the illustration of India, which is a developing country, and also highlights how successful integration of concerns and requirements in the public policy sphere has led to an overall enhancement in poverty reduction. A whopping population of roughly 1.42 billion indicates pressure on the government to elect the right public policy for the millions that can profit the most. India is a developing country but it has achieved a great milestone where nearly 135 Indians managed to escape poverty between 2016 and 2021 with significant progress observed in ‘standard of living’ pointers contributing to positive change. According to a United Nations report, India has witnessed a remarkable achievement of 415 million people coming out of poverty for 15 years. This significant progress represents a positive metamorphosis in the economic and social conditions of a large section of the population. According to IMF research, India had nearly canceled extreme poverty by 2020-21 when food subsidies were considered in. However, some disagreements must be addressed so that India can maintain this progressive line towards achieving SDGs. The major concern is to increase the inclusivity of the programs which can only be achieved through population control and to make way for demographic changes as and when needed in the programs. Population explosion is a major shortcoming on the Indian front as the excessive population is a clear indicator of resource shortages and hinders beneficiary mapping. If the population is at par with country-wise area coverage then it ensures better implementation of policies dedicated to eradicating poverty and makes sure that the policy awareness is stronger by reaching more masses. The next step to paving India’s way towards advancement should be stricter policy measures concerning population control and creating awareness about the disadvantages of population explosion and the advantages of family planning.

Bibliography

“13.5 Crore Indians Escape Multidimensional Poverty in 5 Years.,” n.d. https://pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=1940125.

“Poverty Rate in India Statistics 2022 | Poorest State in India,” July 20, 2023. https://www.theglobalstatistics.com/poverty-in-india-statistics-2021/.

IMPRI. “Ayushman Bharat Digital Mission- Policy Update 2021.” IMPRI Impact and Policy Research Institute, December 19, 2021. https://www.impriindia.com/insights/policy-update/ayushman-bharat/.

Yadav, Sapna, Raghav Sharma, and Marshal Birua. “Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan: Achievements, Problems and Future Prospects: A Comparative Analysis of Some Indian States.” In Springer EBooks, 175–201, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-1414-8_9.

“Data | How Effective Has the Pradhan Mantri Ujjwala Yojana Been,” December 19, 2019. https://www.thehindu.com/data/data-how-effective-has-the-pradhan-mantri-ujjwala-yojana-been/article30338388.ece.

Niti Aayog. Accessed July 25, 2023. https://niti.gov.in/sites/default/files/2023-07/National-Multidimentional-Poverty-Index-2023-Final-17th-July.pdf.

Wider working paper 2021/1. Accessed July 25, 2023. https://www.wider.unu.edu/sites/default/files/Publications/Working-paper/PDF/wp2021-1-MPI-India.pdf.

Article written by Pratyasha Kar | Proofread by Zhangir Zhangaskin